WORKING PAPER

As soon as I was able to secure some ‘research’ time I proposed that I would conduct a preliminary investigation where I would examine the positioning of South Asian Women writers in the UK marketplace pre and post-pandemic.

The basis of this curiosity was my life’s work, as editor of The Asian Writer where I’ve interviewed hundreds of writers and as a small press publisher at Dahlia Books. To say I’ve been frustrated by the lack of progress big publishing has made to address its diversity problem is a huge understatement. I have previously written at length about these frustrations on The Asian Writer. For this research, I wanted to take a deep dive in how big publishing compares with the small presses (who are woefully underresourced) and to a lesser extent better understand the shape and focus of my research.

What I set out to do

At proposal stage I needed to focus my thoughts on what I would actually do and how. I narrowed down my research to the following activities:

a) review the existing literature

b) identify fiction titles written by South Asian women writers and published pre- and post-pandemic (initially I set a 3-year period, which I extended to 4, to include titles published between Jan 2019 – December 2023)

c) collate author bios for these titles

d) collate the jacket covers for the paperback version of these titles

e) identify potential authors for interviews

I was fortunate enough to secure additional internal funding for a research trip which allowed me to visit the British Library where I carried out extensive searches. While I did not set out to write a full literature review I did want to understand the wider context of my research. I also wanted this to be an organic process and an opportunity to learn more about myself and the nature in which research is conducted in academia.

Publishing

Research from Spread the Word (2015) and Saha (2020) highlights the persistent underrepresentation of Black and Asian writers in mainstream literary culture. Despite concerted efforts to address this lack of diversity, the publishing workforce remains 85% white (Publisher’s Association, 2022), and books written by writers of colour are often perceived as niche and therefore not the same value as their white counterparts (Saha, 2020).

Arundhati Roy’s observation that ‘There’s really no such thing as the “voiceless”; there are only the deliberately silenced or the preferably unheard’ challenges misconceptions about the lack of writing talent among diverse voices and rightfully shifts the onus back to the book industry, which for too long has failed to recognise that talent. Recent debate around the need for greater representation in books has helped to reinvigorate efforts from publishers to find and champion new writing talent with schemes such as Penguin’s WriteNow leading the way.

South Asian Women

Research by Wilson and others examining the early experiences of South Asian women in the diaspora (Puwar N, Raghuram P. 2003) provide important historical context on how South Asian women are perceived by the mainstream which may impact on how they are marketed by publishers and ultimately, received by readers.

In her seminal work, Finding a Voice, Wilson (1978) wrote “There have been things written about Asian women which show them always as a group who can’t speak for themselves. They are just treated as objects – nothing more” (p.166). But little had changed twenty years on, when she writes “Although new images have been constructed (of South Asian women), the same perceptions are still influential. Working-class ‘traditional’ Asian women are still seen as of no interest, passive, having no agency whatsoever – waiting to be liberated. And that liberation still means only one thing: ‘westernisation (Wilson, 2006).’

Methods

This research used a mixed method approach using both of quantitative and qualitative techniques.

Suitable fiction titles were identified using popular books to read lists on The Asian Writer and BookRiot, the British Library bibliographic and main catalogues, The Asian Booklist, as well as publisher websites and catalogues, as well as Amazon.

Statistical analysis focused on titles published, genre or category of publication, and the publisher.

Qualitative techniques such as visual rhetoric analysis and content analysis were used to a lesser degree in the research to understand the meaning and messages behind author bios, jacket titles and book cover designs.

This research is limited by the availability of data. Although every effort was made to ensure that all fiction titles were included, it was difficult to gather titles published digitally or by smaller presses, especially in instances where presses have ceased operations.

Further research is needed to understand the experiences of these writers as they navigate the publishing journey.

Key Findings

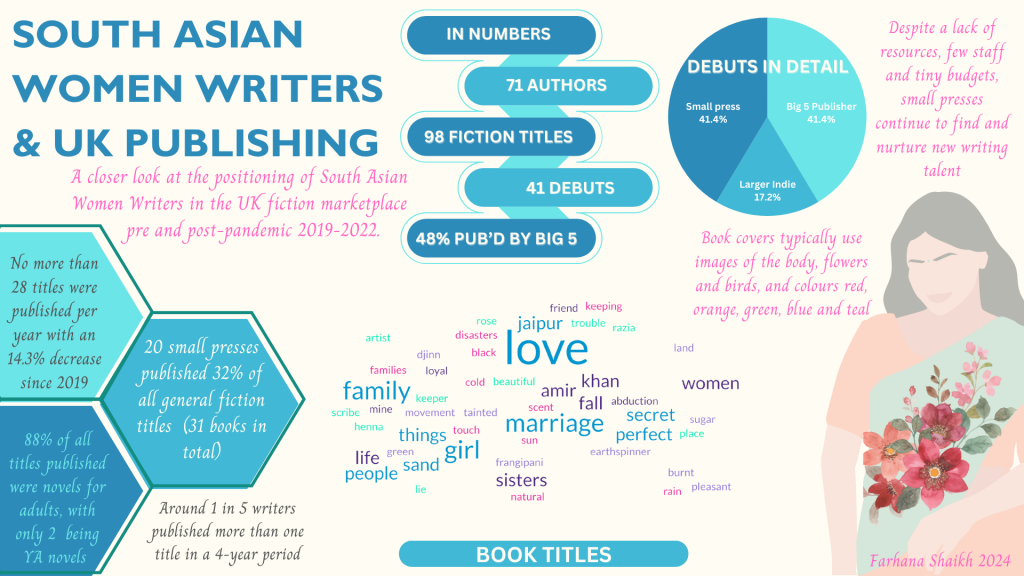

A closer look at the UK fiction marketplace over a four year period (2019-22) found:

In numbers

98 fiction titles were published in total, 88% of these titles were marketed as novels for adults, 2 YA novels, 5 short story collections, and 1 flash fiction collection, novella, novella in flash, novel in translation and graphic novel respectively. 48% of all titles were published by a Big 5 publisher.

Of these 98 titles, there were no more than 28 titles published in any given year (2019), with an expected dip in 2020 due to the pandemic when only 19 titles were published, with an overall decrease of 14.3% in 2022 (23).

A significant proportion of titles (42%) were debuts. Around 59% of these titles published by independent publishers or small presses, 41% published by one of the big 5. 20 small presses published 31 books in total, representing 32% of all titles published.

71 South Asian Women authors were published over a 4-year period, with 20% of these writers publishing more than one title during this time.

Small presses

Despite tiny budgets, few staff, and a lack of resources, the small presses continue to find and nurture new writing talent. At a time of economic crisis, when the pandemic sent shockwaves through the global economy (World Bank, 2022) and bigger publishers were scaling back their publishing outputs, it was the small presses that were going boldly and taking commercial risks, commissioning around 1 in 3 of all titles by South Asian women writers.

Moreover, this research highlights that it is the small presses that are leading the way in publishing work which would be considered to be non-traditional, and more experimental in terms of approach or style, supporting the view by Sunny Singh et al (2017) that the small presses are doing most of the heavylifting when it comes to championing exciting, new voices.

South Asian women writers

The UK marketplace primarily consists of UK based South Asian women writers, followed by authors based in the US and India. A high proportion of South Asian women writers who achieve publication are based in London, with just under 10% stating in their bios that they are former lawyers.

Around 1 in 5 of all South Asian women writers, primarily writing genre fiction, are producing more than one title in a 4-year period. It seems that the shift to digital, in terms of both e-books and audio, and celebrity bookclubs help these writers to establish a wider readership for their work.

The Henna Artist by US author Alka Joshi is currently the most reviewed title on Amazon with 29,356 reviews. It was chosen as Reese’s book club picks which might go some way at explaining that figure! This is followed by The Family Holiday by Shalini Boland (who was also the most prolific author during this period) for her thriller, which received 7,932. Boland is published by Bookouture (a digital publishing company and imprint of Hachette) and lastly, bestselling author and household name Monica Ali’s Love Marriage which has 7,036 reviews.

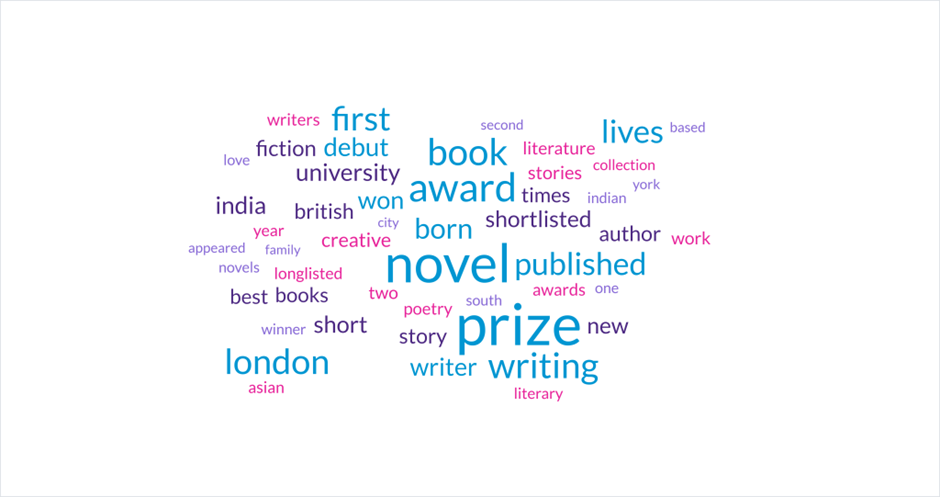

Author Bios

South Asian women writers are positioned in terms of place and achievement. This is evident when looking more closely at the author bios which appear on the book, publisher’s websites and Amazon.co.uk.

Author bios are grounded in place and commonly include words that represent where the author lives (India, Indian, city, London, York, lives, based, British, Asian, South, city).

There is a significant focus on the author’s achievements in these author bios with words such as award, prize, won, awards, shortlisted, longlisted, winner, literary, published that lean into the unhelpful notion that writers of colour must be exceptional to be recognised or published.

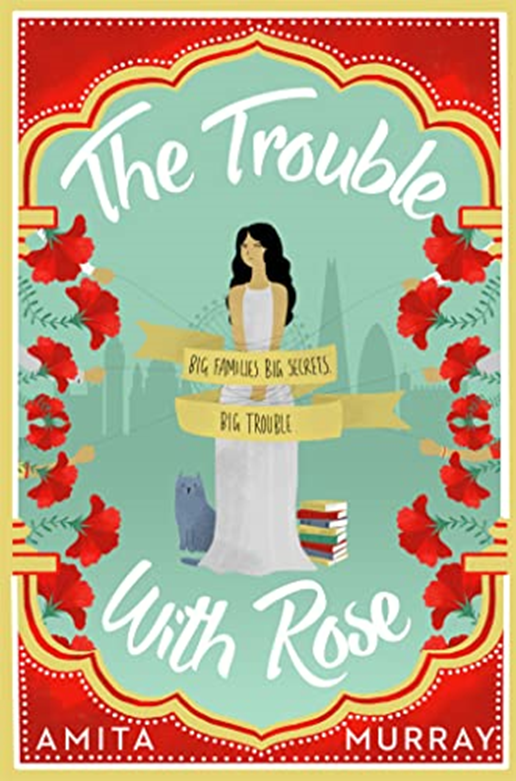

Book Covers

Book covers use images of the body, flowers and birds. Popular colours in books by South Asian women writers include red, orange, green, blue and teal. Depictions of the body can be seen as romanticising, and objectifying the female form. Depending on the proximity of the figure on the cover, it may also hint at mystery or hiding something.

While red is associated with passion, desire and anger, in Indian culture it is also the colour of bridal gowns and thus represents fertility and youthfulness (Smith, 2022). Orange is bold and extravagant, and in popular culture very much at home with Bollywood. Colours orange and green appear on the Indian national flag suggesting that such writers are positioned as Indian writers.

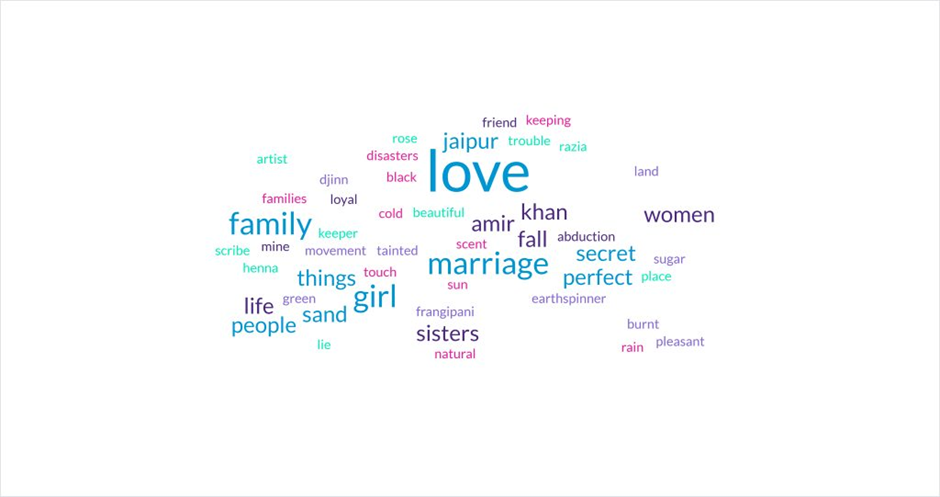

Book titles focus on love and marriage which suggest romance or romantic themes, and centre on femininity with words such as girl, women, sisters used often. Lies and secrets, family and families were also commonly used which hint at mystery and melodrama. Dramatic narratives and melodrama are typically associated with Bollywood storytelling.

What did AI come up with when creating a book cover with the prompt South Asian women book cover? An Asian women sitting with her arms crossed in what looks like monsoon rain *sigh* (created using DeepAI, with keyword South Asian women book cover and selecting Impressionism)

Where to next?

I will work on a full paper and share more findings in due course. I have now also secured research time to expand the scope and nature of my research to consider the impact the small presses have made in championing Black and Asian writers and shaping mainstream literary culture since 2010.